In a recent Wisdom Circle session, participants discussed various strategies we can employ for making our day-to-day work lives more engaging – without changing jobs or companies.

One key insight that’s especially relevant for today’s job huggers: Making our jobs more fulfilling isn’t just about what we do at work. It’s also about how we do it.

Psychologist Peter Gray, in a Substack post titled “When Work Is Play,” notes that if we can find ways to bring more choice and flexibility into our work, craft our jobs in ways that make them more creative and self-directed, and design our work tasks so that they become more intrinsically motivating, we can reframe our job tasks from “have to do’s” to “get to do’s.” We can transform the work we do from toil into play, making our jobs less burdensome and more satisfying.

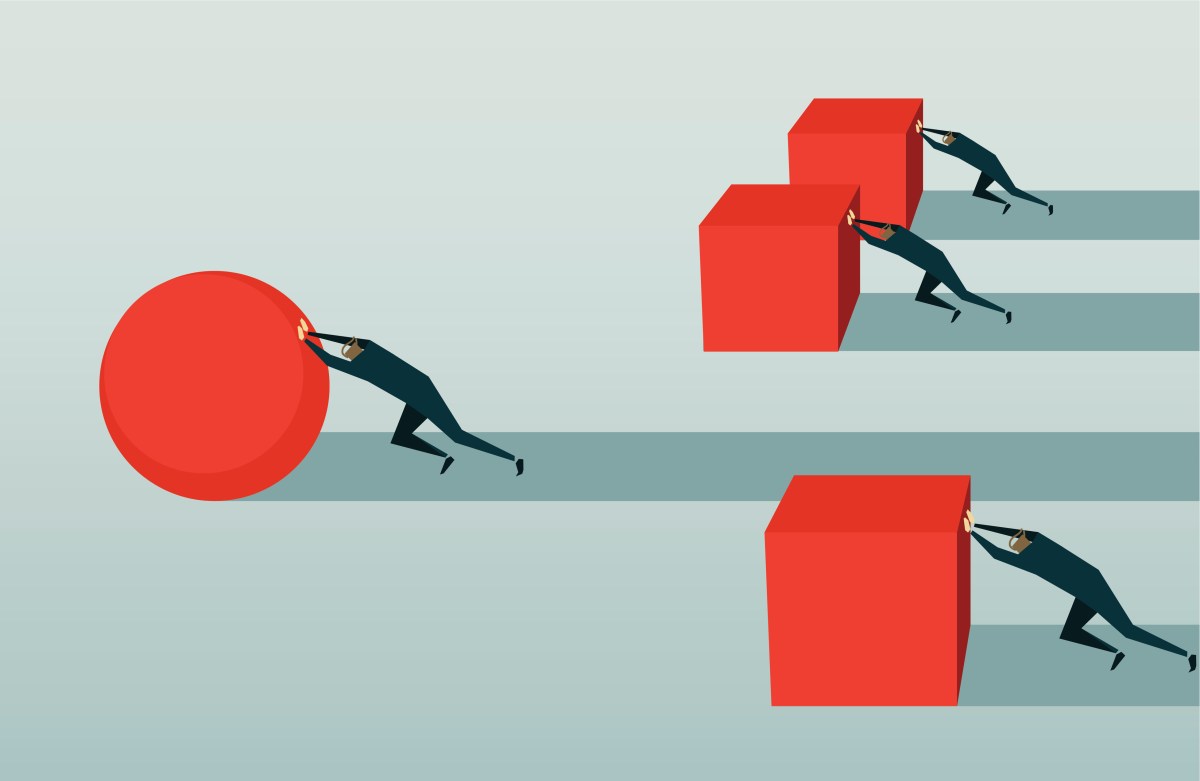

Another insight that emerged from last weekend’s conversation is that we should at all costs avoid multi-tasking, which makes us less productive and degrades the quality of our work.

While we might convince ourselves that we’re getting more done by performing multiple tasks in parallel, our brains are in fact moving quickly back and forth between tasks, which increases our cognitive load because of the time it takes to reorient ourselves back to working on the previous task. Instead of multitasking, we should focus our attention on performing one single task at a time as well as we possibly can so that we can minimize distractions and bring more creativity to our work.

If we can find ways of making our daily work tasks more playful and focus our full attention on one task at a time, we’re much more likely to experience what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow experiences,” which can become a powerful source of happiness and meaning at work